本是同根生:新加坡的马来族群

原文:苏海莉·奥斯曼(Suhaili Osman)翻译·关汝经

多元文化的新加坡

新加坡是一个多元种族的国家,但那许多张新加坡人的脸孔却被笼统地归纳为华人、马来人、印度人,以及模糊不清的“其他”种族。这种“统一”本地种族与文化的方式忽略了每个社群自身的历史与文化,掩饰了新加坡的多元性。多年来,新加坡的教育与语文政策强化了这样的文化定位,同时简单地将现代国人的源头链接到中国、马来群岛与印度。实际上,每个族群都是多元化的,甚至有混杂的语种和方言。

虽然早期新加坡人口普查的方法并不精细,收集到的资料也不可靠,但至少呈现出居住在英国殖民地的不同族群。早期的人口普查将海外华人分成不同的方言群,马来群也分得较细,有马来人、武吉斯人、爪哇人、峇厘人、巴韦安人。在那个年代,来自不同地方的马来人被认定为不同的族群。

由于对英殖民地政府越来越不满,本地的马来人在1926年成立了新加坡马来人联盟(Kesatuan Melayu Singapura) [1]。马来人联盟引发何谓马来人的辩论,团结了来自马来群岛(Nusantara)的族群[2],鼓起民族主义的情绪。

今天,就国家政策与务实的角度而言,“马来人”这个词汇简便地涵盖了所有来自马来群岛的族群。在某个程度上这样的归纳方式并没有错,但若是追源溯流,许多本地马来人还是十分在意“我从哪里来”的文化底蕴。新加坡马来人的集体回忆和所属的社群组织都抵制了政府统一他们的移民历史和文化习俗的做法。各马来社群还是非常重视他们的种族的特殊性,包括语言、习俗与日常生活,以保留他们的根。

以种族为基础的协会和社会机构

19世纪的新加坡以及海峡殖民地成立了许多以族群为首,类似华人的宗乡会馆的组织,它们的首要任务是安顿来自同乡的新客和他们的眷属。本地最古老的马来同乡组织是新加坡巴韦安人协会(Persatuan Bawean Singapura),于1934年3月19日在社团法令下注册[3],并获得殖民地警察总监的鼎力支持。

巴韦安人协会跟族人同心协力,帮助从巴韦安岛移民到新加坡的新客,为他们提供住宿和生活费。那些没有工作的,协会为他们介绍工作。其他来自马来群岛的族群,包括爪哇、武吉斯和米南加保人也陆续组织了非正式团体,直到20世纪下半叶才停止运作。

新加坡米南加保协会(Persatuan Minangkabau Singapura)于1995年8月31日成立,宗旨是维护和促进米南加保文化,同时将米南加保人的习俗与传统介绍给新加坡人与其他人士。

“来自相同的群岛”展览系列

为了促进各马来族群间的相互认识,从2013年底开始,马来传统文化馆[4]着手筹备一系列的常年展览,称为“来自相同的群岛”。相同的群岛为大家缔造一个交流的平台,让各个不同的马来族群呈现他们的文化与传统。马来传统文化馆跟各个文化协会与族群组织合作,共同研究与呈现相关的展览[5]。

第一个展览“时代的变迁:新加坡巴韦安人的遗产和文化”,在2014年3月至8月展出。这是个跟新加坡巴韦安人协会合作的项目,呈现离乡背井的巴韦安人的社会历史与文化习俗。巴韦安是爪哇东北部的一个小岛,早在19世纪,巴韦安人已经来到新加坡定居。

第二个展览“咫尺天涯:登陆后打造一片天空”,在2015年5月17日至9月13日展出。这是个跟新加坡米南加保协会合作的项目,主题是呈现米南加保文化的包容性。

为我们提供资料的巴韦安人、米南加保人和散居新加坡的原族群都深具代表性,他们也渴望让观众感受到他们并非固步自封的社群,与时并进是他们高度重视的文化特性。

在国家与效忠的概念还没有形成的年代,马来世界对“移民”的理解跟今天是不可同日而语的。

“跑江湖”是巴韦安人和米南加保人的传统,不论是贩夫走卒或是年轻人都不惜离乡背井,到异地他乡寻找财富。他们或是在陆地上披荆斩棘,长途跋涉;或是乘着小舟或其他经得起风浪的船只,随着季候风飘泊到爪哇海与印度洋的商港。

早期的米南加保移民则被吸引到商贸和需要劳工的城市。20世纪初,米南加保人将家乡的橡胶、咖啡和烟草带到新加坡销售。他们在西苏门答腊翻越高山丛林,来到东岸的廖内省,续程越过马六甲海峡,抵达新加坡。

巴韦安人四海为家,多代以来累积了丰富的航海知识,船只是他们理所当然的交通工具。巴韦安是爪哇海上的一个小岛,距离东爪哇的首府泗水以北120公里。巴韦安人航行到马来群岛各地,包括新加坡。每逢交易的季节,这些在江湖上跑动的商人就会在各个商港逗留数月,换季的时候才随着季候风回家。

每次成功的回航都会提高这些商人在社群中的地位,丰富的阅历使他们变得更加神奇,吸引了一波又一波的村民离开家乡,到各地区碰碰运气。

群岛的移民文化习俗

没有可靠的资料显示在英国人来到新加坡之前,巴韦安人和米南加保人已经在新加坡定居。19世纪初,巴韦安人开始移民到这里。对前往麦加朝圣的回教徒而言,新加坡是个很好的中途站。巴韦安人和群岛的族群一样,中途过境新加坡攒路费,续程到阿拉伯去。

到了20世纪初,新加坡这个自由港充满无穷的经济生机,移民的浪潮格外蓬勃。早期先民兴建棚屋(ponthuk),接济漂洋过海来到异地,举目无亲的族人,为他们提供短期住宿与社交场所。这些棚屋多数是由富裕的商贾出钱兴建,让来自同村的新客有个落脚之处。

巴韦安人集居在惹兰勿刹与赛阿威路之间的梧槽河畔。许多座落在惹兰勿刹附近的甘榜加卜一带的战前店屋都成为巴韦安人的住家[6]。19世纪的时候,住客多数是男人。住客将月租交给棚屋的首领,这笔钱是租金也是互助金,用来为族人治病、失业救济和缴付罚款等。巴韦安人生活中的大小事由棚屋首领料理,如果住客无法养活自己和家人,首领会提供食物与日常用品。首领和居民之间形成一个社会架构,保证每个人的福利都获得妥善的安排,直至他们找到工作与宿舍,或者已经有经济能力,将家庭接过来,安顿自己的家园。

在跑江湖这方面,巴韦安人和米南加保人有许多相似之处。跑江湖让这些人累积财富与提升社会地位,甚至表示自己已经成人,可以自立了。有句米南加保的谚语:“Dima bumi dipijak, di sinan langik dijunjuang”,它跟马来谚语“Di mana bumi dipijak, di situlah langit dijunjung”是一样的。这句谚语说“你站在什么地方,头顶上就是那里的天空”,也就是入乡随俗,到了罗马就做罗马人做的事。这句话成为米南加保人远洋在外的座右铭。作为一名米南加保人,除了努力地保护米南加保文化,遵守宗教信条之外,也必须跟随当地的风俗与传统。

米南加保人宣称,他们跟其他群岛的移民不一样,他们不会在别人的地方成立米南加保村落。他们更重视融入当地社会,与当地的文化习俗同化。通过一些在本地作出非凡贡献的米南加保人,我们可以对米南加保文化有更深一层的了解。友诺士(Mohamed Eunos Abdullah,1876-1933)是海峡殖民地立法议会的第一位马来委员,也是新加坡马来人联盟的创建人之一。二战英雄阿南少尉(Lieutenant Adnan Saidi,1915-1942)在新加坡的保卫战中英勇抗敌而牺牲。尤索夫(Yusof Ishak,1910-1970)出任新加坡第一任总统,曾经在新闻媒体和公共服务领域任职。

虽然米南加保人被椰加达、廖内、森美兰和新加坡的当地社会同化,但他们拥有坚固的同乡会体系与社会组织。米南加保人是苏门答腊岛上最大的族群,他们的文化是母系继嗣的。一般人认为米兰加保人的财富是继承了妻子的家势,一些学者则认为这些财富来自先民跑江湖所打造下来的基业。表面看来,先人留下的遗产,已经足以使女人和后代高枕无忧。

在母系社会里,女人继承祖先的土地与财产,后裔可以通过女系追溯他们的族谱。母系社会分成不同的部落,再进一步划分为家族。每一个部落由一名长老出任族长。同样的,每个家族也由一名长老担任家长。米南加保跟其他群岛社群不同之处,在很大程度上是一个平等的社会,经济角色分工明确。在习惯法下,女人掌管土地与产物,男人负责公共行政与领导宗教事务,例如族长与家长。

米南加保的习俗有两个分支,第一支奉行的是阶级制度(kelarasan Koto Piliang),另一支奉行的是平等的观念(kelarasan Bodi Caniago),它们在米南加保的社会体系中相辅相成。此外,米南加保通过历史的认识与尊重(Tungku Tigo Sajarangan)来维护和发展米南加保的节日、祭祀和文化。宗教专家、知识分子和长老拥有相等的地位,社区的相关事宜都通过这三组人磋商来取得共识。

巴韦安人的社交网络与社群关系则体现在棚屋文化里。巴韦安人和米南加保人一样,通过协商来维系社会秩序与和谐。凡是促进融洽的工作,整个社群都会守望相助,一同参与。这些活动包括筹备婚姻,割礼仪式以及治理丧事。这种特殊的特质已经成为本地马来社会的代名词,新加坡政府甚至将这种互助精神提升为国家长远的愿景。

新加坡在19世纪至20世纪初发展加冷与新加坡河口,甘榜与商业中心近在咫尺。马来语作为这个时期的区域语言,自然成为民众交谈的日常用语。群岛的移民开始“异族通婚”,接受伴侣的文化习俗。在这个海港城市生活的居民如爪哇人、巴韦安人、武吉斯人、米南加保人、峇厘人和班加人,至少在表面上看不出它们之间有什么差别,他们信奉相同的伊斯兰教,注意饮食和得体的穿着,显示出群岛族群有相同的文化而不是分野。

虽然伊斯兰教是群岛社群的共同宗教,大家遵守相同的道德价值观,每个族群还是保留着自己的风俗文化与独特的表演艺术。许多年长的爪哇人、巴韦安人、米南加保人和班加人还使用母语交谈。米南加保语跟马来语非常相似。

米南加保人的传统习俗与习惯法都通过文学的形式流传下来,包括故事、传说、班顿(诗歌)和谚语。在重要的社交场合如社群节日,米南加保人会致欢迎词;向对方的家庭提婚的时候,必须吟诵美丽的班顿。这一切都凸显了米南加保人继承了祖先的传统,喜欢展示演说的才华。

同样的,巴韦安人对他们的传统口头表演深感自豪。新加坡的巴韦安人在马六甲海峡居住下来,受到其他语言的影响。他们的巴韦安语跟原地的巴韦安语有点不同,演变成本地化的石叻巴韦安语。有趣的是,巴韦安人将许多阿拉伯与伊斯兰教的元素并入他们的传统文化表演。手鼓和歌舞表演穿插了口述故事、回教徒的仪式、划一的动作和中东风格的节拍和旋律。这些音乐演出通常在家庭聚会、婚礼和宗教仪式上进行。

马来语的经济角色和方言的保存

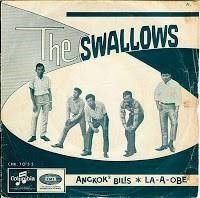

巴刹马来话(Melayu pasar)和新马的学校传授的正统马来文(Bahasa Melayu)是各马来群岛族群的沟通语言。1960年代,有一支可爱的新加坡五人“燕子乐队”(The Swallows)使用巴韦安语灌录了“Laaobe”(不一样的时光)专辑。唱片封套印上“La-a-Obē”,其中一首以披头士的音乐改编的“pop yeh-yeh”在1966年首次通过电台播出。这支充满动感的乐队,凭借充满魅力的队员Kassim Selamat (1934-),红遍新马。值得一提的是,燕子乐队跟EMI签约后,成为本地娱乐杂志的宠儿,经常在电视上露面。“Laaobe”声名远播,甚至流行到当时的西德。

同一时期,许多巴韦安人在娱乐圈闯出名堂,成为著名的演员、表演家和唱片红星。多才多艺的Saloma (Puan Sri Datin Amar Salmah binti Ismail,1922–1983)是名声大噪的歌手兼影星,Sanisah Huri、 Salim I、A Romzi 、 Jaafar O这些1960-1970年代的名歌星都是巴韦安血统。直至今天,“Laaobe”依旧是新马巴韦安人的代名词。

很不幸的,当今的新加坡马来人通晓米南加保、巴韦安、爪哇和其他群岛的母语的新一代并不多,不过一些原来的文字与词语还在继续使用,补充马来文的的不足。

马来人的身份认同

大家了解了米南加保和巴韦安两个马来社群的历史与丰富的文化传统,可以进一步想象新加坡马来社群的复杂性。本文绝不是为了将马来世界的各族群归类成划一的文化和语言,这是因为无论研究巴韦安人、米南加保人、爪哇人、武吉斯人、班加人、峇厘人、亚齐人或曼特宁人,到头来都会面对“谁是马来人”这个相同的问题。

东南亚历史学者和钻研马来世界的学术界人士,包括Anthony Reid、Leonard Andaya、 Anthony Milner 和 Virginia M. Hooker,就马来人的起源追溯到公元二世纪的埃及托勒密王朝[7]。

有证据显示“马来(巫来由)” (Melayu/Malayu)这个词汇来自远古,但无法确定马来这个地方到底在何处。中国从公元7世纪开始便使用“马来”,指的是室利佛逝或三佛齐(Sivijaya),马可波罗则称之为Malayur。室利佛逝乃1290年左右苏门答腊的古王国[8]。

即使马来文献对于马来王朝的确实地点也交代得模糊不清。《马来纪年》中的马来指的是马来王和马来文化,不过巫来由的所在地竟然是神话般的西衮当山(Bukit Siguntang)和小小的巫来由河(Sungei Malayu)。更有趣的是,巫来由并不是目前学者所指的苏门答腊、巨港或占碑这些马来王朝的据点,因为古代中国、印度、阿拉伯和欧洲旅客都称这些地方和当地人为爪哇或爪夷。

相反的,16世纪的马六甲称“马六甲人”为“马来人”。《马来纪年》和《汉都亚传》使用“马来人”来代表那些马六甲“马来苏丹”的支持者 [9]。当1511年葡萄牙攻占马六甲时,昔日的马来苏丹的追随者纷纷在这个区域寻找新的出路。那些流落各地,讲马来话的侨民依旧保留着“马来”文化与身份认同。他们对马来苏丹忠心耿耿,觉得自己是“马来人”,宣称自己是马来人。因此,何谓马来人的界限是相当灵活的。

到头来,来自马来群岛,不同根源的新加坡马来人必须在多元种族的社会寻找共同点。表面上,在新加坡的马来政体中,各马来族群并没有身份认同的问题,但是,无论是爪哇人、巴韦安人、米南加保人或其他族群,民族特性将继续存在。

马来传统文化馆由衷感激新加坡马来社群赐予这份殊荣,能够一起庆祝源远流长的马来文化传统,并期待跟爪哇社群一起筹备2016年的“来自相同的群岛”系列展。

参考资料

Timothy P. Barnard (ed.), Contesting Malayness: Malay Identity across Boundaries (NUS Press, Singapore, 2004)

Phyllis Ghim-Lian Chew, A Sociolinguistic History of Early Identities in Singapore: From Colonialism to Nationalism (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012)

展览资料

Laaobe: Warisan dan Budaya Masyarakat Bawean di Singapura (Changing Times: Baweanese Heritage and Culture in Singapore) which ran between March and August 2014.

Marantau: Dima Bumi Dipijak, Di Sinan Langik Dijunjuang (Coast to Coast: Atlasing the Sky Wherever One Has Landed), which runs from 17 May to 13 September 2015.

[1] 新加坡马来人联盟的成立,被认为是导致马来半岛原政治生态下形成其他类似性质的组织的源头。

[2] 以现代的说法,“马来群岛”指的是马来-印尼群岛,Nusantara是旧爪哇文,包含两个根词:“群岛”(nusa)和“之间”(antara)。

[3] 新加坡巴韦安人协会在1947年重新注册,将原来的Persatuan Bawean Singapura Association改为Persatuan Bawean Singapura。Association跟Persatuan是重复的文字。

[4] 2012年9月,马来传统文化馆重新对外开放,在甘榜格南的前苏丹胡先皇宫设立了永久展厅。19与20世纪的甘榜格南是个繁忙的商港,人来人往,商贸发达,并引导访客进入关键性的层面:谁是新加坡的马来人?这里不是要提供结论性的答案,而是鼓励大家通过多维的角度和当代马来人的身份来思考此问题。

[5] 合作的模式是让个社群的工作伙伴负责制定展览的内容,联系社群,收集文物,对他们是个崭新的体验。马来传统文化馆提供专业建议与资料。社群伙伴也制定展览的其他节目,这是他们的强项,因此这些节目都充满活力,令人振奋,跟整个项目融成一体。

[6] 例如Pondok Diponggo, Pondok Kalompang Gubuk, Pondok Tachung, Pondok Teluk Dalam, Pondok Paromaan, Pondok Sangkapura, Pondok Keleam and Pondok Tandel。

[7] Anthony Reid ‘Understanding Melayu (Malay) as a Source of Diverse Modern Identities’. Timothy P. Barnard (ed.), Contesting Malayness: Malay Identity across Boundaries (NUS Press, 2004),第三页提到,托勒密的‘Golden Khersonese’地图加入了爪哇文‘Melayu Kulon’,也就是“西巫来由”。

[8] 同上

[9] 同上

(作者为马来传统文化馆助理研究员)

异族同心6版

图片请参考英文版,并将英文版作为附录排成7版(不要图片)

Serumpun/ Roots of the Same Tree: Ethnic Malay communities in Singapore

Suhaili Osman, Asst Curator, Malay Heritage Centre

A multicultural Singapore

When Singapore is presented to the world as a multi-racial or multi-ethnic country, the ‘many faces of Singapore’ inadvertently fall under the ‘Chinese-Malay-Indian’ (CMI) and nebulous ‘Others’ administrative categories. This rubric (at least the CMI part of it) of easily identifiable ethnic-cultural categories has tended to gloss over the real diversity of Singapore’s polity, along with each ethnic community’s respective histories and cultural heritage. Various language and education policies over the years have tended to reinforce the neat categorisation of cultures in Singapore at the same time they create a pseudo-link to respective ancestral homelands of China, the Malay Archipelago and India – which realities are a cacophony of language groups and dialects across multiple ethnic communities.

Although the methodology was rough and the data unreliable, the early censuses of the Singapore population taken during the 19th century listed separate figures for the various ethnicities who were residing in the British territories. Just as the British censuses differentiated the overseas Chinese by their dialect groups, they also distinguished between Malays, Bugis (or ‘Buginese’), Javanese, Balinese and Baweanese (‘Boyanese’), indicating that these communities were perceived as distinct ethnic groups at the time.

In 1926, as a response to growing disaffection with colonial administration, the Kesatuan Melayu Singapura (Singapore Malay Union or KMS) was set up. The KMS[1] sparked debate on defining a Malay identity which would unify the aforementioned ethnic groups from the Nusantara[2] with the effect of stimulating nationalist sentiments. Today, as a matter of state policy and practicality, ‘Malay’ (and Malay/Muslim) has become the convenient catch-all for those of Nusantaran ancestry, promoting the notion of homogeneity within the community. While this may hold true to some extent, the deeper and longer roots of a plural ethnic and cultural heritage still matters to many Malays here. The collective memories and agency of successive generations of Malay-Singaporeans have resisted the bureaucratic homogenisation of their migrant histories and cultural practices. By continuing to observe their ethnic particularities, dialects and customs in quotidian life, the diasporic Malay sub-ethnic communities have strived to preserve their distinct ethno-cultural markers to varying degrees of success.

Ethnic-based associations and social institutions

Many clan and ethno-cultural associations were established in 19th century Singapore (and the Straits Settlements at large) for the primary purpose of extending aid to the newly-arrived fellow village kinsmen or relative to the respective colonial port towns. The oldest of the Nusantaran associations, Persatuan Bawean Singapura (PBS), was initially registered on 19 March 1934 under the Societies Act as the Persatuan Bawean Singapura Association.[3] PBS was formed to assist and supervise all the ponthuks or Baweanese communal houses which were scattered all over the island at that time and its establishment received strong support from the then British Commissioner of Police in Singapore. PBS worked together with the ponthuks in assisting the newly arrived migrants from Pulau Bawean, providing shelter and sustenance as well as assisting them to find employment in Singapore. Other Nusantaran communities, namely the Javanese, Bugis and Minang also formed less formal associations until the latter half of the 20th century. The Persatuan Minangkabau Singapura (Singapore Minangkabau Association – SMA) was established on 31 August 1995 with a mission to preserve and promote the Minangkabau culture in Singapore as well as to introduce and educate on Minangkabau customs and traditions to Singaporeans and non-Singaporeans.

Persatuan Bawean Singapura (PBS) committee members, 1930s. Courtesy of The Baweanese Association of Singapore

The Se-Nusantara Series

To address this diversity, the Malay Heritage Centre (MHC)[4] started work on an annual exhibition series titled Se-Nusantara (‘Of the Same Archipelago’) in late 2013 to extend the discourse set out in its permanent exhibition. The Se-Nusantara series serves as a platform for the various sub-ethnic groups to represent themselves as MHC would partner with cultural associations or community organisations to co-curate an exhibition with accompanying programmes.[5]

The first exhibition of the series was Laaobe: Warisan dan Budaya Masyarakat Bawean di Singapura (Changing Times: Baweanese Heritage and Culture in Singapore) which ran between March and August 2014. It was co-curated with PBS and featured the social history and cultural practices of the Baweanese who left their ancestral homeland, a small island off the north eastern coast of Java, and came to settle in Singapore since the 19th century. The second exhibition, Marantau: Dima Bumi Dipijak, Di Sinan Langik Dijunjuang (Coast to Coast: Atlasing the Sky Wherever One Has Landed), which runs from 17 May to 13 September 2015, focuses on the integrative aspects of Minangkabau culture and was co-curated with the SMA.

Both the Baweanese and the Minangkabau resource peoples who MHC worked with in the Se-Nusantara series were highly attuned to the diasporic origins of their respective communities in Singapore. They were also eager to impress upon the audience that the outward-looking perspective was a highly-valued cultural trait of the community. In a time before nation-states and national allegiances, the conceptualisation of migration in the Malay world is quite different from how it is understood today.

Postcard of a group of affluent Baweanese with their servants, Singapore, 1910. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board

The Minangkabau and the Baweanese both refer to the cultural practice of merantau – when traders, merchants or young men seeking their fortunes – left ancestral villages either via arduous overland routes or with the monsoon winds on perahus and other such sea-worthy vessel to make for bustling port towns in the Indian Ocean and Java Sea. Early Minangkabau migrants were attracted to urban areas where trade and wage-labour opportunities are found. In the early 1900s, Minangkabau men travelled to Singapore, looking to trade home-grown produce such as rubber, coffee and tobacco. The traditional route taken was an arduous land route from West Sumatra over rugged terrain to traverse the Riau mainland to get to the eastern coast of Sumatra before continuing the journey over sea. For the Baweanese who were traditionally seafarers, sailing ships were the default mode of transportation to sail from their small island located in the Java Sea approximately 120km north of Surabaya, the capital of East Java, to different parts of the archipelago, including Singapore. The bazaars and markets which sprouted and folded with each trading season meant that many of these itinerant merchants and traders spent several months in each port-town, travelling to and fro their homelands with each monsoon. With each successful return, one’s standing in the community increased and stories about the places they made their fortunes grew even more amazing, enticing successive waves of village kinsmen to make their own luck.

A perahu bawean such as this would have been used to merantau to other parts of the Malay archipelago. Courtesy of Mr Osman Jonet.

Adaptative strategies and cultural practices of Nusantaran migrants

While there are no reliable records as to how early the Baweanese and Minangkabau started settling in Singapore prior to European colonial presence in the region, the Baweanese started migrating to Singapore as early as the 19th century. Singapore’s position as a transit point for Muslim pilgrims on the way to the holy city of Makkah in Arabia, saw many Baweans (along with other Nusantaran groups) ply their trades here to make enough money for the onward sea passage. The waves of migration intensified in the early 20th century due to the vast economic opportunities available in the British free port. The early arrivals set up a ‘ponthuk’ (Malay: pondok), a communal lodging house which served as a temporary residence as well as a social institution organized along village lines of traditional authority. These ponthuks were usually established by the most materially wealthy early immigrants and aided new arrivals seeking work from their own ‘desa’ or kampong (village).

The Baweanese migrants settled along the bank of the Rochor River between Jalan Besar and Syed Alwi Road. Many pre-war shophouses located around Kampong Kapor Road near to Jalan Besar were turned into ponthuks such as Pondok Diponggo, Pondok Kalompang Gubuk Upper Weld Road), Pondok Tachung, Pondok Teluk Dalam, Pondok Paromaan, Pondok Sangkapura, Pondok Keleam and Pondok Tandel. Largely male up until the 19th century, the ponthuk residents paid a monthly fee to the ‘pak lurah’ or ponthuk chief, that covered more than just rent – it entitled him to certain rights of association – including a place to turn to in bad times such as ill health, employment dismissal or even traffic fines. If he had no means to support himself and his family, the pak lurah supplied him with meals and other necessities. Essentially the ponthuk communal residence formed a social structure that ensured the individual’s welfare was taken care of until they found employment and on-site lodgings or were economically secure enough to bring their families over to Singapore and set up their own homes.

The Pak Lurah of Ponthuk Kalompang Gubuk, Haji Hatip (at the extreme right), at an akad nikah (marriage solemnization) ceremony, Ponthuk Kalompang Gubuk at Upper Weld Road,1985. Courtesy of Hjh Junaidah Bte Junit

There are some similarities in the practice of merantau between the Baweanese and Minangkabau in terms of it being a means to increase one’s wealth and hence social status as well as a male rite of passage. However, rather than birthing a system of communal residences abroad, ‘marantau’ as it is called in Baso Minang, instead highlights the assimilative traits of the Minangkabau emigrants. A Minangkabau proverb, ‘Dima bumi dipijak, di sinan langik dijunjuang’ has an identical rendition in Malay – Di mana bumi dipijak, di situlah langit dijunjung. The meaning of the proverb (“to carry the sky upon one’s head wherever one sets foot on”) is akin to the adage, “When in Rome, do as the Romans do”, and serves as a guiding philosophy for the Minangkabau who journey to new lands. Thus, even as a Minangkabau strives to live by his/ her religious tenets and preserve Minangkabau cultural norms, he/ she should adhere to and uphold the local customs and traditions.

A group photograph of a Minangkabau family, c. 1890-1920. Courtesy of the Tropenmuseum Collection.

The Minangkabau hence claim that unlike other diasporic Nusantaran communities who set up enclaves in their adopted countries, one would not encounter a Kampung Minangkabau in foreign parts as the community emphasises integration into and assimilation with the local culture. The enactment of this ideal is probably best exemplified by the prominent Minangkabau figures featured in this section, who have made significant contributions to the community-at-large and Singapore. Illustrious Minangkabau pioneers include Mohamed Eunos Abdullah (1876-1933), who was the first Malay member on the Straits Settlements Legislative Council and co-founder of the Singapore Malay Union, WWII hero Lieutenant Adnan Saidi (1915-1942) who sacrificed his life defending Singapore against the Japanese and independent Singapore’s first president, Yusof Ishak (1910-1970), whose career spanned both the journalistic world and public service.

Nonetheless even as the Minangkabau assimilate into local societies on Java (namely Jakarta), the Riau islands, in Negeri Sembilan on the Malay Peninsula and Singapore, they hold steadfast to a clan-based matrilineal system of social organisation. Considered to be the largest surviving society in which lineage and property are inherited through married females, some scholars have attributed this to the marantau practice where ‘harato pusako’ (ancestral property, Malay: harta pusaka) is naturally left in the hands of those who do not have to leave them behind. Thus, the welfare of the women and future generations is ostensibly ensured.

A matrilineal way of life is one where descent is traced through the female line, and where women inherit ancestral land and property. Based on the matrilineal lines, the society is divided into suku, or ‘clans’, which is further sub-divided into perut, or ‘lineages’. Each suku is headed by an elder known as the Lembaga, while an elder known as the Buapak heads the perut. Unlike other Nusantaran communities, Minangkabau society is largely an egalitarian one with a clear division of economic roles. Both men and women are custodian of adat, the customary laws, with women managing the land and rights to the harvest while men hold public political and religious leadership such as that of the Lembaga and Buapak.

Whereas the Baweanese social networks and community relationships are embodied in the institution of the communal ‘ponthuk’ or pondok, there exists two ‘kelarasan’ or branches within the Minangkabau adat system. The first, kelarasan Koto Piliang, is based on hierarchy while the second, kelarasan Bodi Caniago, demonstrates a more egalitarian outlook. These two branches serve to complement each other and form the Minangkabau societal system. In addition, three community pillars known collectively as Tungku Tigo Sajarangan, safeguard and develop Minangkabau ceremonies, rituals and culture. They consist of the religious experts, the intellectuals and the elders occupying equal ranks. Community-related matters are expected to be resolved through consensus-building among the three groups.

Both ethnic communities value a governance-by-consensus approach is maintaining social order and harmony. This cultural ideal is underscored by another time-honoured cultural practice of gotong royong (co-operative undertakings) where the entire community pitches in, both materially and morally to complete a task which is deemed desirable to promote congenial relations amongst members of the group. Such activities include preparations for a wedding (through rewang and kendarat duties), rite-of-passage such as the bersunat or berkhatan ceremonies (ritual circumcision) as well as funeral arrangements. Indeed, this particular trait has become so synonymous with the larger Malay community that Singaporean officials have come to adopt the term wholesale to refer to the desirability of cooperative effort on a national platform.

As Singapore further developed its ports in Kallang and the mouth of the Singapore River through the 19th and early 20th century, the relative close proximity of the various kampungs to the commercial hubs translated into daily interactions which were usually conducted in Malay, the regional lingua franca of the period. Many of the Nusantaran emigrants also began to marry across ethnic lines and adopt some of the cultural practices of their spouses. To the other inhabitants of the bustling port-city of Singapore, the Javanese, Baweanese, Bugis, Minangkabau, Balinese and Banjarese did not seem to be very different from one another, superficially at least. The shared religion of Islam which meant that many observed the dietary laws and modest dress reinforced the notion that these Nusantara communities were culturally more similar than different.

However, even as Islam serves as a common religious culture as well as a set of overarching moral values across many of the Nusantaran groups, each ethnic community maintained many of the cultural practices, material culture as well as performing arts unique to their respective region. Many of the elder Javanese, Baweanese, Minangkabau and Banjarese continue to converse in the regional tongue amongst themselves. The Minangkabau people speak a language called Baso Minangkabau which is closely associated with the Malay language. Their customs and traditions or adat are encoded in vast collections of oral literature in the forms of kaba (traditional stories), tambo (legends), pantun (quatrains) and pepatah-petitih (proverbs and sayings). Pidato (welcome speeches) are usually recited and exchanged at major social events, such as makan bajamba (communal feasts), while flowery pantun exchanges are virtually de riguer during merisik expeditions (when a suitor’s representatives calls on a family to seek a maiden’s hand in marriage) and weddings. This lively exchange of banter and pithy sayings is termed as jual beli (buy-sell), showcasing the Minangkabau love for oratory whilst alluding to the trading and entrepreneurial roots of many of its people.

A makan bajamba Minangkabau communal feast. MHC had hosted a similar event as part of its the educational programme to promote Malay regional cultural heritage. Source: m.mimangkabaunews.com

In a similar fashion, the Baweanese are proud of their oral performance traditions. The Baweanese speak ‘Bahsa Bawean’ (or Bahasa Boyan), which is considered to be a dialect of Madurese. However, the Baweanese in Singapore speak a slight variation, boyan selat, referencing their settled location along the Malay Straits. Interestingly, the Baweanese, more than any other Nusantaran group have also incorporated many Arabic/ Islamic elements into their traditional cultural performances. Hadrah (hand drum processions) and kerchengan performances combine Baweanese storytelling, Muslim devotion, synchronised body movements and Middle-eastern styled beats and melodies. These musical performances are conducted both in the home usually during a keramaian (gathering) as well as part of a wedding or religious procession.

The economic role of Malay language and the preservation of regional dialects

Bazaar Malay (Melayu pasar) and increasingly formalised Bahasa Melayu that was taught in national schools in Malaya then (and Singapore and Malaysia today) became the language of communication amongst these ethnic communities. Hence it is a lovely irony that in the 1960s, a popular Singapore 5-member band, The Swallows, scored a hit with their Baweanese-language record, ‘Laaobe’ (Changed). Originally printed as ‘La-a-Obē’ on their vinyl sleeve, the catchy ‘pop yeh-yeh’ song (in the vein of The Beatles’ tunes), was first broadcast on the Singapore airwaves in 1966. The dynamic band, with its charismatic front man, Kassim Selamat (né Kassim Rahman, born 1934), became one of the popular acts in the mid-1960s in Singapore and Malaysia. The Swallows, who were signed by recording label EMI, were noteworthy for the amount of media attention they received from local entertainment magazines, television appearances and that ‘Laaobe’ was also well received as far afield as then-West Germany.

Album cover of the Swallows’ famous hit ‘La-A-Obe’. Courtesy of Mr Kassim Selamat.

In the same period, many Baweanese also made their mark as actors, performers and recording artistes, including the luminous Puan Sri Datin Amar Salmah binti Ismail (1922–1983) or better known by her stage name, Saloma. Sanisah Huri, Salim I, A Romzi and Jaafar O were very popular singers in the 1960s-70s of Baweanese ancestry. Till today, the refrains from ‘Laaobe’ remain synonymous with the Singapore-Malaysian Baweanese.

Unfortunately, very few of the current generations of Singapore Malays of Minangkabau, Baweanese, Javanese and other Nusantaran ancestries are conversant in their ethnic languages. Nonetheless a number of indigenous words and phrases remain in circulation and are used to supplement the Malay vocabulary which is deemed wanting at times to convey all the nuances of the word in the native language.

Discourses on ‘Melayu’ and its implications on formulating Malay identity

The preceding paragraphs have provided a glimpse into the history and rich cultural heritage of two sub-ethnic groups that make up the intricate tapestry of what is considered the Singapore-Malay community. The article is by no means an attempt to ‘fix’ or pigeonhole the various ethnic communities who consider themselves part of the alam Melayu (Malay world) into neat cultural and/or linguistic categories. The reason is especially because implicit in any study of Baweanese, Minangkabau, Javanese, Bugis, Banjarese Acehnese and Mandhailing ethnic community, is the question, who then is ‘Malay’? Historians of Southeast Asia and those who study the alam Melayu, including Anthony Reid, Leonard Andaya, Anthony Milner and Virginia M. Hooker have gone to great lengths to ascertain the origins of Melayu, a reference used as early as the 2nd century CE in Ptolemaic Egypt.[6]

Documentary evidence suggests that the term ‘Melayu’/‘Malayu’ has ancient origins though no one has been able to pin point the exact location of ‘Malayu’. Chinese records from the 7th century make references to a specific kingdom north of Sivijaya while Marco Polo had identified as ‘Malayur’, an ancient kingdom on Sumatra around 1290.[7] Even Malay-language sources are vague about the location of the Malayu kingdom – the Sejarah Melayu refer to Malay kings and adat (culture) but the geography of Melayu are cited as a mythical Bukit Siguntang and small Sungei Malayu. Interestingly, the term ‘Melayu’ itself was not used to refer to the indigenes of Sumatra, Palembang or Jambi where current scholarship posits as where an ancient Malay kingdom stood. Rather, Chinese, Indian, Arab and European visitors to the archipelago referred to the area and locals as ‘Jawa’, ‘Yava’ or ‘Jawi’.

In contrast, the term ‘orang Melayu’ gained currency in 16th century Melaka as an alternative reference to ‘orang Melaka’. Arguably, in both the Sejarah Melayu and Hikayat Hang Tuah, the term ‘anak Melayu’ refers to the supporters of the Malay sultanate of Melaka.[8] Hence, when Melaka fell to the Portuguese in 1511, the erstwhile followers of the Malay sultanate left for other port states in the region. The diaspora who spoke Malay, who still identified with the ‘Malay’ cultural values and felt a sense of loyalty as the Sultan’s people, saw themselves as ‘Melayu’ and would proclaim themselves as such. In that regard, the boundaries of what defined someone as ‘Malay’ were quite flexible and as much defined by other constituencies of each port city as it was by his or her own agency.

Ultimately, the manner in which Singapore-Malays of the various Nusantaran ancestries negotiate their diverse historical ethnic roots against a multi-racial socio-political and yet ethnically homogenised within each overarching racial category, point to how ethnic particularities continue to matter even though none of the Javanese, Baweanese, Minangkabau and other sub-ethnics have little problem identifying themselves with the larger Singapore-Malay polity. The MHC is honoured to be part of the effort to celebrate the deep cultural heritage of the Singapore-Malay community and looks forward to working with the Javanese community in the next instalment of the Se-Nusantara series in 2016.

References

Timothy P. Barnard (ed.), Contesting Malayness: Malay Identity across Boundaries (NUS Press, Singapore, 2004)

Phyllis Ghim-Lian Chew, A Sociolinguistic History of Early Identities in Singapore: From Colonialism to Nationalism (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012).

Exhibitions

Laaobe: Warisan dan Budaya Masyarakat Bawean di Singapura (Changing Times: Baweanese Heritage and Culture in Singapore) which ran between March and August 2014.

Marantau: Dima Bumi Dipijak, Di Sinan Langik Dijunjuang (Coast to Coast: Atlasing the Sky Wherever One Has Landed), which runs from 17 May to 13 September 2015.

[1] Regarded as a proto-political organisation which led to the formation of other organisations of a similar nature up and down the Malay Peninsula

[2] This term has been adapted into modern parlance to refer to the Malay-Indonesian Archipelago. It is an old Javanese word comprising two root words: nusa (islands, homelands) and antara (between).

[3] It was re-registered in 1947, dropping ‘Association’ to remove the redundancy in its name.

[4] The MHC reopened in September 2012 with a revamped permanent exhibition focused on the site-specificity of the centre which is housed in the former istana (palace) of Sultan Hussein Shah and his descendants within historic Kampong Gelam. The core narrative presents Kampong Gelam as a port town during the 19th and 20th centuries, foregrounding the circulation of goods, peoples and ideas within and without this island, leading to the key question raised in the Perintis (Pioneers) gallery of who the Malays are in Singapore. The aim here is not to reach for a conclusive answer but to encourage considerations of the multiple dimensions and historical construction of the contemporary Malay identity.

[5] The working model for each project is for the community partner to take ownership by developing the exhibition content (often a new experience for them) including garnering artefact loans and other contributions from the community while MHC lends support in terms of technical expertise and resources. The community partner would also produce the accompanying programmes, which is typically the forte of these organisations and hence, the programme offerings are vibrant and exciting, and form an integral component of the entire project.

[6] Anthony Reid ‘Understanding Melayu (Malay) as a Source of Diverse Modern Identities’, in Timothy P. Barnard (ed.), Contesting Malayness: Malay Identity across Boundaries (NUS Press, 2004), p.3. Ptolemy included the toponym ‘Melayu Kulon’, meaning ‘west Melayu’ in Javanese on the west coast of his map of ‘Golden Khersonese’

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid., pp.4-5.

-500x383.jpg)

-500x383.jpg)