闪光灯下:通过旧照片追踪新加坡印度族的历史

原文:苏海莉·奥斯曼(Suhaili Osman)翻译·关汝经

印度族是新加坡的第三大族群,占总人口的百分之九。印度先民来自印度次大陆的不同地区,有各自的宗教信仰与文化习俗。东南亚区域的印度族群来自数波的移民潮:殖民地前、殖民地时期、后殖民地时期。殖民地前,淡米尔纳德邦的雀替尔族商人早在14世纪已经来到马六甲,跟当地的马来女子通婚,并为印度洋各地的商贸作出贡献。不过真正持续性的移民潮是槟城、马六甲和新加坡海峡殖民地成立之后(1786-1824)。印度人从马德拉斯(Madras,金奈)、纳格伯蒂讷姆(Nagapattinam)、加尔各答(Calcutta)的港口出发,越过印度洋,来到海峡殖民地。

1819年1月,120名原属孟加拉步兵团的印度兵跟随莱佛士和法夸尔抵达新加坡。R.B.Krishnan所搜集的资料显示,当时来到新加坡的印度人有Sangara Chetty、Naraina Pillay、 Mohamed Hassan 和 Mohamed Lebar。1822年,法夸尔委任他们为理事,主管印度人的事务[1]。

档案照片为我们提供可靠的线索,得以追踪19世纪末至20世纪初来到新加坡的印度移民。G. R. Lambert 是当时本地著名的相馆,为1867年至1900年代初的新加坡摄下大量珍贵的图片[2],保存着两个世纪前的新加坡的地貌和多元种族的景观,让我们重新探索曾经在这里生活过的不同族群、时尚和习俗。如John Falconer所说:“这些照片加强了东方人的浪漫形象与各族群的神秘感,其中不乏叫人咂舌的镜头。”[3]

这些图片都是为欧洲人精心设计的。在印度,当地画家早已画下这些人文景观。17至19世纪间,印度有许多绘画学校,将印度原住民的肖像、作业、习俗和服饰通过画笔记载下来,满足洋人强烈的好奇心。

本文通过私人收藏家与国家博物馆收藏的G. R. Lambert的照片,追溯本地印度族群的历史。

早期定居的先民

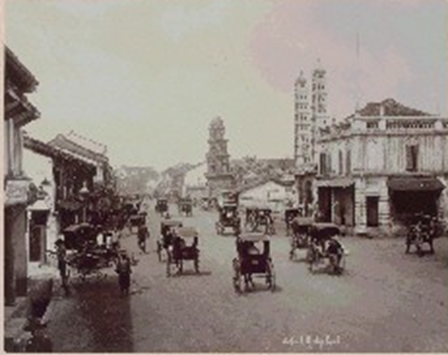

就如Siddique 和 Puru Shotam(1982)所说[4],印度人定居的地方与所从事的职业是相互影响的。早期的企业家在新加坡河岸活动,于是印度人居住在克罗士街(Cross Street)、马吉街(Market Street)、马六甲街(Malacca Street)、莱佛士坊(Raffles Place)等地。这些地方的变化实在太大了,我们已经无法看到印度先民在这里生活的蛛丝马迹,朱烈街(Chulia Street)是唯一的标记。小印度则保留了历史氛围。[5]

19世纪初,来自印度的客商抵达新加坡,朱烈人是其中一个最早抵岸的族群。朱烈人是来自乌木海岸的淡米尔回教徒,他们带来的商品五花八门,有纺织品、珠宝、牛只、皮革、烟草、锡制品和槟榔。那些拥有船只和货船的朱烈人也搞船运。除了淡米尔回教徒,其他淡米尔族群、古吉拉特、马拉巴尔和帕西商人很快的来到海峡殖民地定居,并将新加坡河岸转型为贸易站。这些商人来往于其他英国殖民地,在亚洲和其他地区建立庞大的商业网络。

移民的轮廓

19世纪末和20世纪初,新加坡的印度人到相馆拍照,身上穿着传统服饰,但采用欧洲风格的家具作为背景。这类照片将早期移民的生活静态化,无法看出他们的居住地点和职业。不过,这些影像至少记录了那个年代的移民的穿着、族群构成和社会背景。

19世纪中叶至20世纪初的印度移民以男性居多,那个年代缺乏举家移居海外的动力。国家博物馆收藏了一张20世纪初的淡米尔家庭合照,一家大小穿戴着传统服装和珠宝。

罪犯劳工

1825至1873年间,新加坡是个惩罚印度罪犯的地方。在那50年间,有1万5000至2万名印度监犯被遣送到新加坡当苦力,建设了好些还保留着的建筑地标如总统府、白礁灯塔、莱佛士灯塔、汤申路和武吉知马路。一位名叫Baawajee Rajaram的绘图员,甚至在服刑期间为兴建圣安德烈教堂撰写计划书,服刑期满后成为一名私人建筑师。

殖民地政府在1873年取消囚犯劳工政策。一些前囚犯经营小本生意,买土地建房屋。有些人在公共工程局工作,熟练的工匠担任管工的职务。一些前囚犯当水管工、裁缝、印刷工人、鞋匠、切割机员等,有些则成为食物承包商或洗衣店老板。

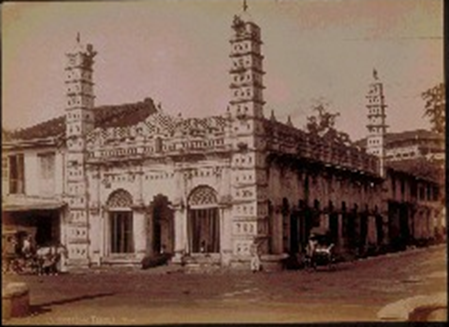

另一个印度先民的特色是兴建宗教庙宇,1820年代落成的马里安曼庙和詹美回教堂都是印度人对新加坡早期建筑的贡献。

安全部队

1881年,新加坡成立了锡克族警察特遣队,第一支部队来自旁遮普(1881年3月26日)。锡克警察分布在马来亚各地,维持当地的法律与秩序。部队于1945年解散。

此外,丹戎百葛船坞公司维持了一支警察部队,成员包括锡克人。1930年代,三巴旺海军基地和实里达空军基地都由锡克警察看管。锡克人也从事保安和看守员工作。锡克人是英国派来海峡殖民地的印度兵成员之一。印度独立后,辜加兵团取代印度兵的任务。

19世纪中叶,受英文教育的印度和锡兰人受聘为殖民地辅政大臣办公室的工程师、测量师、文员和翻译员。印度人也担任火车站管理员、铁路监工、通讯工程、医疗人员和学校教师。20世纪中叶,专业人士如医生、律师、作家、记者从印度来到海峡殖民地。

商业社群

18与19世纪的欧洲经济腾飞,带动东南亚的商贸。雀替尔人从纳德邦移居到缅甸、越南、柬埔寨和马来亚。新加坡河是新加坡的货运中心,货仓与贸易商行林立。1820年代,雀替尔人成为新加坡最早的民间放贷者,在新加坡河附近的朱烈街、马吉街和马六甲街经营放贷业务。在现代银行与金融体系发展起来前,雀替尔人是为殖民地各阶层人士提供中长期借贷的主要贷款商,客户包括欧洲种植园主、华人矿工和商人、马来皇室和农民,印度商人和承包商等。

雀替尔人也是当年主要的地主。他们将货仓改建,店屋的底层设立借贷服务,楼上则装置成多个床位的宿舍。每三年,他们回去家乡探望亲人。到了20世纪初,有些雀替尔人将家人接过来,在海峡殖民地定居。

20世纪初,新马的锡克族也提供个人借贷服务。锡克人跟雀替尔人不一样,他们移民到本地原本从事保安工作。锡克人在市区里当看守员兼借贷人,贷款给劳工、书记和店员,贷款数额低但利息高。他们成立了锡克借贷人和商人协会。

音乐家,舞蹈家和艺人

20世纪初,新加坡已经有印度舞蹈、音乐和舞台演出。淡米尔与帕西的流动表演剧团从印度来到海峡殖民地。新加坡的淡米尔剧团于1930年代成立,表演历史剧。到了1940年代,演出内容逐渐改变,以社会与时事为题材。

印度人乐团如Ramakrishna Sangeetha Sabha成立于1939年,由男女乐师组成。来自锡兰的淡米尔族群成立了纯女子乐团,二战前在新加坡及海外公演。新加坡印度人艺术学会成立于1949年,是最早主办本地与外地艺术表演的团体之一。

印度人在马来电影的发展史上贡献杰出,直至上世纪中叶,他们担任过马来电影导演,也经营过电影发行业务。当时的两大影业巨头邵氏和国泰克里斯聘请印度片导演如B. S. Rajhans、 P. L. Kapur、 B. N. Rao、 Phani Majhumdar、L. Krishnan等人拍摄马来影片。印度人拥有并经营戏院,钻石戏院的主人是K. M. Oli,首都戏院由Namazies管理。Gian Singh & Co是早期的影片发行商。

19世纪末期,印度流动商人开始涌现。实龙岗路及其周边的街道有许多传统业者,如洗衣店、金铺、珠宝商、铁匠、香料研磨和送奶工等,其中不乏流动小贩、乐手、杂技家和舞蹈演员。

泰国甲米有一面刻着婆罗米文的石碑,显示了淡米尔金匠可能早在公元3或4世纪已经移居泰国南部,这或许是印度金匠大规模来到东南亚的最早证据。纳德邦的金匠在1940年代来到新加坡,住在实龙岗路的昏暗的小房间里。金匠根据传统与宗教的需求打造金饰。在一些传统的场合如穿耳洞,金匠都会在场。当机械逐渐取代人工作业时,印度金匠跟着消失,被印度与华族首饰商取代。

女人

过去的新加坡印度族群,男人一路来都处于领导地位,女人则没有什么记载。殖民地文件显示,19世纪中叶来到本地的女人都是囚犯和种植园工。19世纪末,海峡殖民地的印度商人和移民开始将家眷接过来。1920年代,入境的印度妇女约占百分之三十,奠定日后印度侨民落地生根和组织家庭的基础。

印度女子主要是家庭主妇,倾向于社区服务与手工艺品制作。她们充分利用时间,学习针线活、绘画、音乐和舞蹈。有些印度妇女融入本地的土生文化,不论是衣着、语言或美食都入乡随俗。

直至1990年代,女相师替人算命,供应商销售家庭用品、农产品和自制产品等都是小印度司空见惯的风景线。上世纪中叶,来自纳德邦的女回教徒也是闻名的香料商贩。E. A. Ponnammal女士(1898-1973)是一名淡米尔妇女,早在上世纪初已经在本地经营放贷业务,为自己的族群提供资金,并受到其他借贷商的认可。

随着时代的进步,提升妇女地位的意识日渐普遍。1931年,印度与锡兰女子俱乐部成立,支援本地妇女与孩童的教育、社会与经济,为他们提供平等的机会。1950年,印度总理尼赫鲁访问新加坡期间,印度与锡兰女子俱乐部跟妇女联盟合并,成立卡马拉俱乐部(Kamala Club),一直持续至今。

文化习俗

宗教是印度族群文化的根源,印度移民将他们家乡的宗教信仰带到新加坡,兴建庙宇让族人的心灵有所依靠,同时有个聚集的场所。桥南路的马里安曼庙(1827)和詹美回教堂(1830-1835)、直落亚逸街的纳宫神社(1828-1830)都是历史悠久的庙宇。如Sunil Amrith所说:“历史学者通过古老的建筑与文化,找到珍贵的移民记录。这些古老的记载遍布亚洲,为我们提供追寻移民足迹的线路。”[6]

马里安曼庙根据南印度庙宇的建筑风格建成,纳宫神社则完全复制了印度的纳宫神社。当年的旅客都会到神社祈求一路平安。今天,我们还可以在神社内看到一套印度纳宫神社的复制文件。在守护神的纪念日当天,可以观看跟印度纳宫神社同时进行的升旗仪式。

殖民地年代的旧照片反映了“复杂的印度移民史在各族群间缔造了多元化、充满动感的异地风情”[7]。在寻根的路上,我们可以通过语言、宗教、习俗、穿着和食物料理分辨来自印度次大陆不同地区的族群。无可否认的,新加坡的印度人就跟东南亚各地的印度人一样,在进取的过程中融入当地社会,吸收当地的文化与习俗。过去与现在的移民经验促进了印度族群的凝聚力,这些共同的体验进一步加强了本地与世界各地的印度社群的联系。

[1] Krishnan, R.B, Indians in Malaya, A Pageant of Greater India: Malayan Publishers, 1936.

[2] Liu, Gretchen, Archival Collections of Asia Photographs in Singapore’s National Archives, National Library and National Museum; Volume 4, Issue 1: Archives, Fall 2013

[3] John Falconer, A Vision of the Past: A History of Early Photography in Singapore and Malaya, The Photographs of G.R.Lambert & Co., 1880-1910: Times Editions, 1987

[4] Sharon Siddique and Nirmala Puru Shotam, Singapore’s Little India: Past, Present and Future, Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 1982.

[5] Nalina Gopal, Encounters with the Public Archives & Collective Memory: Researching the Indian Community in Singapore, http://library.ifla.org/id/eprint/249

[6] Sunil Amrith, Migration and Modern Diaspora in Asia: Cambridge University Press: 2011

[7] Brij V. Lal, Peter Reeves, Rajesh Rai Encyclopaedia of Indian Diaspora: Institute of South Asian Studies, Singapore: 2006

(印度文化中心研究员)

异族同心5版

图片请参考英文版,并将英文版作为附录排成6版(不要图片)

Glimpses: Tracing the history of Indians in Singapore through Archival Photographs

Nalina Gopal

Curator, Indian Heritage Centre

Indians form the third largest ethnic group in Singapore. Accounting for over 9% of the population, they trace their roots to various regions and religious groups in the Indian subcontinent. The presence of Indians in the region is the result of several waves of migration, pre-colonial, colonial and post-colonial. For instance, prior to European colonisation, Chitty traders from Tamil Nadu had already settled in Malacca in the 14th century, married local Malay women and contributed to the Indian Ocean trade. But it is with the establishment of the Straits Settlements of Penang, Malacca and Singapore (1786 -1824) that a steady influx of Indians from the subcontinent began – primarily via the ports of Madras, Nagapattinam and Calcutta. In January 1819, 120 sepoys landed in Singapore, together with Sir Stamford Raffles and William Farquhar. They belonged to the Bengal Native Infantry and were accompanied by a bazaar contingent. R.B.Krishnan notes that among the earliest Indian migrants in Singapore were Sangara Chetty, Naraina Pillay, Mohamed Hassan and Mohamed Lebar; they were appointed as counsels to oversee matters relating to the Indians by William Farquahar in 1822.[i]

Archival photographs offer glimpses of Indian migrants in Singapore from the late 19th to the early 20th century. The firm of G. R. Lambert & Co operated from 1867 until the early 1900s and produced the single most important pictorial record of Singapore in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[ii] These included scenes of Singapore and its multi-racial residents. These photographs reiterated stereotypical Western visions of the East by capturing racial types, costumes and customs. As John Falconer puts it ‘In these photographs a number of attitudes coexisted, among them a reinforcement of the romantic image of the East peopled by the mysterious races and spiced with danger’.[iii] They were images choreographed largely for the consumption of a European clientele. In the Indian subcontinent such imagery was already being produced by local artists. Between the 17th -19th centuries, a unique school of painting developed in India at many centres. Portraits of Indian natives, taken by officers of the Company or later by Indian artists known collectively as Company School Paintings served to quench the curiosity of Europeans on native subjects. They included trade studies and documented customs as well as costumes.

This essay traces the history of the Indian community in Singapore through select photographs from private collections as well as the G.R.Lambert & Co studio (currently in the collection of the National Museum of Singapore).

Early Settlement

Early entrepreneurial ventures and activity centred on the river front; occupation and settlement intertwined as also posited by Siddique and Puru Shotam (1982) that settlement and occupational patterns of Indians in Singapore evolved together. However, much of the early settled areas such as Cross Street, Market Street, Malacca Street, Raffles Place, etc have altered in character bearing little visible evidence of Indian occupation; the name in some cases such as Chulia Street being the only marker. In this context, Little India retains much of its historic atmosphere.

Early entrepreneurial ventures and activity in Singapore centred on the river front; occupation and settlement intertwined, as observed by Siddique and Puru Shotam (1982).[iv] That is, the settlement and occupational patterns of migrants in Singapore evolved together. However, many of the early areas settled from India, such as Cross Street, Market Street, Malacca Street, Raffles Place, have altered in character and now bear little visible evidence of former Indian business occupations; the name in some cases, such as Chulia Street, being the only marker. In this context, Little India does retain much of its historic atmosphere of settlement along the lines of occupation.[v]

View of Singapore River, Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore

Traders and merchants arrived in Singapore during the early 19th century; one of the earliest groups to arrive was the Tamil Muslims (or Chulias) from the Coromandel Coast. They traded in a wide range of commodities including textiles, gems, cattle, leather, tobacco, tin and areca nuts. They were also involved in water transport as several of them owned ships and cargo boats. In addition to the Tamil Muslims, other Tamil (Vellalar, Mudaliar, etc), Gujarati, Malabari and Parsi traders soon settled in the Straits Settlements and transformed the Singapore River banks into a trading hub. Travelling between and trading with other colonial settlements, these traders and merchants were instrumental in establishing networks within and beyond Asia.

Migrant Profiles

Portrait of an Indian Family taken by G.R.Lambert & Co, Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore

Portraits of Indians in Singapore taken in the late 19th and early 20th century show them in studio settings with European style furniture and backdrops, dressed in traditional costumes. De-contextualised from their place of dwelling or occupation, these photographs portray early migrants in a still, life-less fashion. However, these portraits serve as a visual record of the mode of dress, the ethnic composition and the social background of migrants of the time. In the above photograph for instance, an archetypal Tamil migrant family is seen in traditional garb and jewellery. The majority of Indian immigrants to Singapore from the mid-19th century till the early 20th century were male, with the impetus for migration of families only growing later. The following explores trade study photographs and elaborates on the the history of early Indian settlers in Singapore.

St.Andrew’s Cathedral, Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore

Convict Builders

Singapore was a penal settlement from 1825 – 1873 and during this period, nearly 15,000 – 20,000 prisoners were sent here as convict labour. These labourers built some of Singapore’s earliest architectural landmarks like the Istana, Horseburgh Lighthouse, Raffles Lighthouse etc. as well as roads such as Thomson and Bukit Timah roads. A convict draughtsman, Baawajee Rajaram, even prepared plans for the St.Andrew’s Cathedral and went on to pursue private architectural practice upon completion of his sentence.

With the dispersal of the penal settlement in 1873, several former prisoners started small businesses, and bought land and property. A number of them sought employment with the Public Works Department (PWD) and the skilled artisans amongst them were appointed as overseers for the PWD. Some former prisoners also found work as plumbers, tailors, printers, shoemakers, stone-cutters, etc. while others became food vendors or set up sundry shops.

The settlement pattern of early Indians in Singapore was also characterised by the construction of structures which catered to their religious needs. Built in the 1820s, temples such as the Sri Mariamman Temple and the Jamae Chulia are examples of the contributions of Indians to Singapore’s early architecture.

Portrait of Sikh Policemen, Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore

Security Forces

In 1881, the Sikh Police Contingent (SPC) was established in Singapore, with the first contingent arriving from Punjab on 26 March 1881. The SPC were stationed all over Malaya to assist with the maintenance of law and order; following the Second World War, the SPC was disbanded in 1945. In addition to the SPC, the Tanjong Pagar Dock Company maintained a Dock Police Force composed of Sikh recruits. By the 1930s, a Sikh police force emerged at the naval base in Sembawang and another one at the Royal Air Force airbase in Seletar. The Sikhs also found employment as security guards (jagas) and watchmen for private employers. The Sikhs were also an integral part of the British Indian forces posted in the Straits Settlements and were in charge of maintaining law and order; they were replaced by the Gurkha contingent in Singapore on Indian independence.

English educated Indians and Ceylonese were recruited from the subcontinent by the mid – 19th century; to be engaged as engineers, surveyors, clerical officers and interpreters in the Colonial Secretary’s office as railway station masters, supervisors for rail, road and telecommunication works as well as health workers and school teachers. By the mid-20th century, medical and legal practitioners writers and journalists from the subcontinent also began to establish themselves in the Straits Settlements.

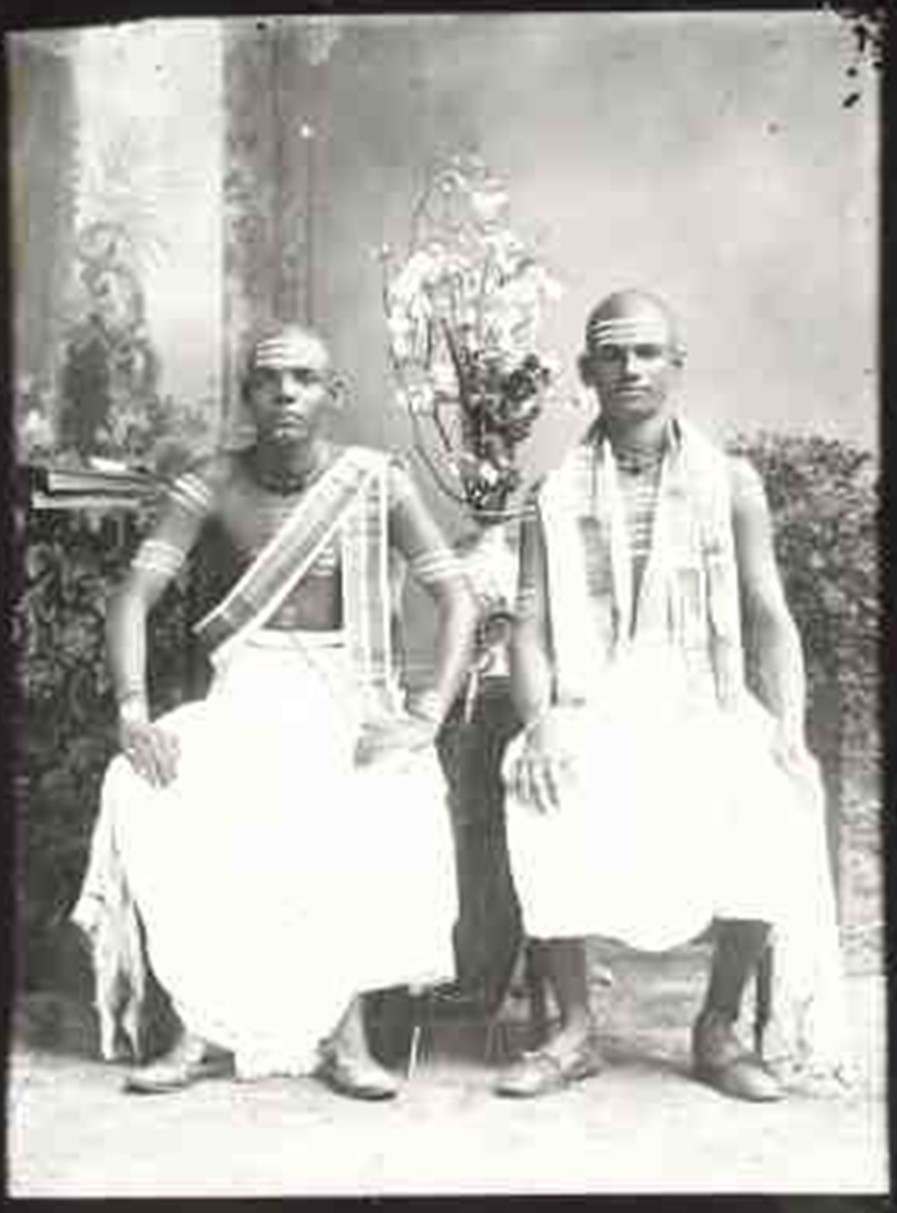

Portrait of two Chettiar men, Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore

Merchant Communities

During the 18th and 19th centuries, when European trade flourished, another community from Tamil Nadu of Nattukottai Nagarathar Chettiars migrated to Southeast Asia including the Straits Settlements, Burma (Myanmar), Indo-China (Vietnam), Kampuchea (Cambodia), and Malaya (Malaysia). The earliest presence of Indian moneylenders in Singapore can be traced to the 1820s. The Chettiars established their financial operations along Chulia, Market and Malacca Streets along the Singapore River where cargo landed and many warehouses and trading firms were located.. Traditionally a trading community, the role of the Chettiars as private financiers grew widespread in the European colonies. The Chettiars were also principal landowners and functioned as the main source of medium and long term credit until the advent of modern banks and the growth of the co-operative movement. The Chettiars operated out of kittangis (Tamil: warehouse) set up in the ground floor of shop houses; with dormitory style lodgings were organised in the upper floors. Once in three years, they travelled back to Chettinad to visit their families; by the early 20th century there are instances of Chettiars settling with their families in the Straits. Their clientele included European proprietary planters, Chinese miners and businessmen, Malay royalty and farmers, Indian traders and contractors, among others.

Personal financing was also extended by Sikh moneylenders in Singapore and Malaya in the 20th century. The Sikhs unlike the Chettiars migrated as security personnel. They operated in urban centres in Singapore as watchmen cum money lenders, who extended small loans to labourers, clerks and small shopkeepers at premium interest rates. A Sikh Money Lenders and Businessmen’s Association was also established in the early 20th century.

Musicians, Dancers and Entertainers

A group of travelling performers taken by G.R.Lambert & Co, Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore

Indian dance, music and theatre have been performed in Singapore since the turn of the century (if not earlier). By the early 20th century, travelling drama companies from the Indian subcontinent were performing in the Straits Settlements and these included early Tamil and Parsi theatre companies. Tamil theatre in Singapore dates from the 1930s and started off with historical plays before shifting their focus to social issues and current affairs during the 1940s.

Orchestras such as the Ramakrishna Sangeetha Sabha were established as early as 1939 and included both male and female musicians. An all-women’s orchestra was also established by members of Ceylon Tamil community, and performed at public venues in and around Singapore in the pre-World War II years. The Indian Fine Arts Society (later renamed Singapore Indian Fine Arts Society), established in 1949, was among the early organisers of performances by travelling as well as local troupes and artistes.

Indians also contributed to the development of Malay cinema by directing and distributing Malay films until the mid-20th century. Production houses such as Shaw and Cathay-Keris engaged Indian film directors such as B. S. Rajhans, P. L. Kapur, B. N. Rao, Phani Majhumdar, L. Krishnan etc. Early Indian owned and managed theatres included Diamond Theatre owned by K. M. Oli Mohamed and Capitol Theatre managed by the Namazies while early Indian film distributors included Gian Singh & Co.

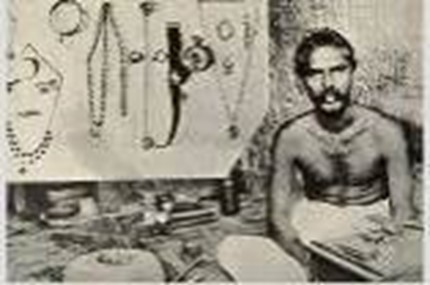

Portrait of Indian Goldsmiths at Serangoon Road, Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Indian itinerant tradesmen also operated in the late 19th century. Serangoon Road and its surrounding streets housed traditional tradesmen such as launderers (dhobie), goldsmiths and jewellers, black smiths, spice grinders and milkmen etc. as well as itinerant food sellers, musicians, acrobats and dancers.

A 3rd or 4th century Tamil Brahmi inscription found in Krabi, Thailand hints at the migration and settlement of a Tamil goldsmith in southern Thailand. Perhaps this could be earliest evidence of the influx of Indian goldsmiths to the Southeast Asian region. Pathars or acharis, the goldsmiths from Tamil Nadu began entering Singapore in the 1940s. Housed in little dark back rooms along Serangoon Road and its by-lanes, the goldsmiths soldered and shaped gold and ornaments according to tradition and religious requirements. The goldsmith was also often present at traditional functions such as the ear-piercing or kadu-kuthal being just one of them. With machine made jewellery slowly overtaking the meticulous handiwork, the Indian goldsmiths were replaced by retailers, both Indian and Chinese.

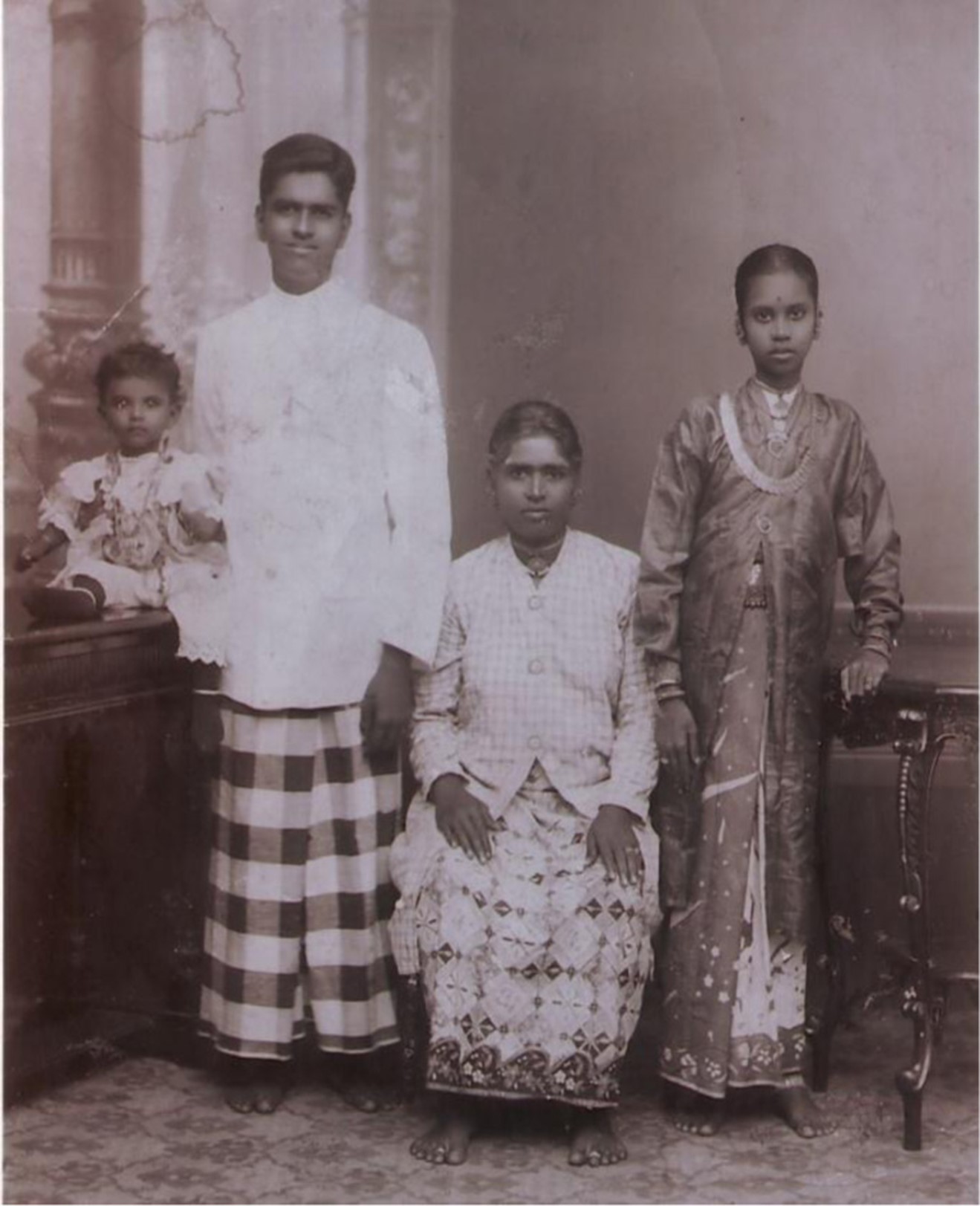

Mdm Alameloo Pillay with Family, Courtesy of Chitra Radhakrishnan

Women

The narrative of Singapore’s Indian community is generally male dominated; chronicles of women are mostly obscure. By the late 19th century, Indian traders and independent migrants to the Straits Settlements were joined by their families. Colonial documents do record women as penal inmates and plantation labourers during the mid-19th century. Indian women accounted for 30% of the arrivals by the 1920s, laying the foundation for permanent settlement and family structures.

Women were essentially homemakers, inclined towards community work, arts and crafts. They learnt needlework, painting, music, and dance and employed their time creatively. Some of these women were also strongly influenced in their style of dress, language and cuisine by local Peranakan cultures. Itinerant women fortune tellers, vendors selling domestic wares, farm and homemade products were a common sight around Serangoon road area until the 1990s; Kadayanallur Muslim women, for instance were renowned spice sellers in the second half of the 20th century. Yet another example is Madam E. A. Ponnammal (1898- 1973) an early was a Tamil lady who operated a money lending business in the early 20th century in Singapore. She is accredited with funding businessmen from her community, the Agamudayar Davar, in Singapore.

Modernisation and widespread increase in awareness about women’s rights resulted in the formation of women’s associations in Singapore. The Indian and Ceylonese Ladies Club, established in 1931, was an early organised effort to support women and children in the fields of education, social and economic upliftment and provide them equal opportunity. It was later renamed Lotus Club to accept membership from other ethnic groups. Subsequently, in 1950 during the visit of the Indian Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, the Lotus Club and another women’s organisation the Ladies Union were merged to form the Kamala Club, which continues to this day.

Cultural Practice

Sri Mariamman Temple and Masjid Jamae at South Bridge Road, Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore

Nagore Dargah, Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore

Religion is an important aspect of the community’s root culture that migrants brought with them to Singapore. An important aspect of their religious expression was the construction of places of worship; these also served as places of gathering for the community. By the mid-19th century, significant shrines such as the Sri Mariamman Temple (1827) and Jamae Chulia (1830 – 35) at South Bridge Road, the Nagore Dargah (1828 – 30) at Telok Ayer Street, among others had been erected. As explained by Sunil Amrith ‘historians find a valuable archive of migration in the landscape, in architecture and in material culture. Everywhere scattered across Asia, are material traces of migration’[vi]. While the Mariamman temple was built following south Indian parameters for temple architecture, the Nagore Dargah was constructed as a replica of the Nagore Dargah in India. Dedicated to the patron saint, Shahal Hameed, the Dargah in India would be visited by travellers, praying for safe passage. An emulation of the proceedings held at the Dargah in India can be seen in Singapore even today; the kodi yetram or flag hoisting festival held annually at the Dargah coincides with the festivities in India, marking the anniversary of the patron saint.

Archival photographs from colonial Singapore reflect the ‘complex history of emigration has produced a diverse and dynamic religious tapestry in the Indian diaspora’.[vii] Indians in Singapore trace their roots to various regions of the Indian subcontinent. This diverse group is distinguished by its varied linguistic, religious and other socio-cultural practices such as dress, cuisine, etc. Indians in Singapore, like Indians in other parts of Southeast Asia, have also adapted and evolved, absorbing traits from local cultures. Past and present migrant experiences make this community cohesive; its connections with the larger global Indian diaspora strengthened by such shared experiences.

[i] Krishnan, R.B, Indians in Malaya, A Pageant of Greater India: Malayan Publishers, 1936.

[ii] Liu, Gretchen, Archival Collections of Asia Photographs in Singapore’s National Archives, National Library and National Museum; Volume 4, Issue 1: Archives, Fall 2013

[iii] John Falconer, A Vision of the Past: A History of Early Photography in Singapore and Malaya, The Photographs of G.R.Lambert & Co., 1880-1910: Times Editions, 1987

[iv] Sharon Siddique and Nirmala Puru Shotam, Singapore’s Little India: Past, Present and Future, Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 1982.

[v] Nalina Gopal, Encounters with the Public Archives & Collective Memory: Researching the Indian Community in Singapore, http://library.ifla.org/id/eprint/249

[vi] Sunil Amrith, Migration and Modern Diaspora in Asia: Cambridge University Press: 2011

[vii] Brij V. Lal, Peter Reeves, Rajesh RaiEncyclopaedia of Indian Diaspora: Institute of South Asian Studies, Singapore: 2006

-500x383.jpg)

-500x383.jpg)